Author Archives: Infinite Ideas

Poker face

14 January 2014 by Infinite Ideas in Book publishing

by Anne-Marie Cockburn, author of 5,742 Days

I’m not pretending, no poker face could disguise this, but admittedly I haven’t given the ‘bereavement’ adequate space despite it constantly vying for my attention – like two fighting siblings in the back of the car. ‘Muuumm, he’s squashing my leg’ … ‘Would you two stop it now – be nice to your sister’. Give me sparkly tinsel over a sobbing heap on the floor any day. ‘Give tinsel space’, I say, as the bereavement says ‘Ho, ho, ho’ and waits patiently in the corner.

I go to a Christmas lunch at a pub on Sunday. Everything looks appropriately cosy and inviting as we sit at our table for ten. The Christmas CD has been dusted off and is duly played on repeat and the Christmas tree, of a height the room is unable to accommodate, has a slight bend at the top – there’s no room at the inn for you 4 inches, said the innkeeper, you need to find somewhere else to stay, we’re full.

All the ingredients for a lovely Sunday lunch and enjoyable afternoon are mixed in the pot and lovingly stirred around, there, there. I feel it pulling at me; my eyes glaze up and I try to stop it – not now, not in a room full of happy people wearing Christmas hats and full of Christmas cheer, don’t do this now. Snap, the cracker is pulled and out I fall. I sob and can’t stop; I bend my head forwards and am glad of the ample cloth napkin to dry my tears. ‘Someone put a finger in the dam and save us all from drowning’, I wish. Jingle bells, jingle bells – the tune distorts in my head and sounds sinister. I realise I’ve exhausted myself for weeks by fighting the inevitable. Oh but what a good fight I’ve put up, I think as I sit in the corner of the boxing ring having blood wiped from my nose, waiting for the bell to ring again. Ding, ding, here we go, I think as I stagger to my feet, round two.

I feel as though my head is full of cotton wool; friends try to comfort me. They know as well as I do that there are no answers and they can’t make me feel better. Some find it hard to make eye contact with me and I don’t blame them as the pool of dark sadness that exists behind mine can reach into their soul and render them tarnished by witnessing what I’m going through. I look out from the stage at an empty audience; I can make out the vague figure of a cleaner hoovering with her back to me. ‘She’s behind you’, I shout out, but my call comes out silent. I laugh to myself then lie down on the stage to die, but then I hear the distant sound of hooves and suddenly a knight in shining armour comes galloping towards me. He’s coming to rescue me, I think. He stops his horse dangerously close and asks if I know the way to Sleeping Beauty’s Castle; typical, I think. I lie down on the stage to die again, my life flashes in my head page by page, I feel the wind from the pages turning, rippling gently across my face.

There’s so much to take in: there we are, my girl and I, with her giggle lighting up the stars and fuelling the sun. Chapters showing struggle, love, friendship, travel, hope and dreams – so much to take in. I stand back and gaze at it all – wow, it’s incredible, with nature as the quietly confident backdrop to it all, being ignored by many, but never complaining and getting on with it regardless. I peer out from one eye, ‘Am I dead yet?’, I ask rhetorically. I know ‘my’ book definitely hasn’t ended and there are many chapters to go from here. But I’m so incredibly tired, so I lie between two chapters, the text from the written/lived pages leaving an imprint on my bare back, with the unwritten/unlived ahead of me. I curl up and rest a while, recharging for the journey ahead. As I wake, I reach up and pull down the blinds as the winter darkness has returned prematurely again. An elderly man walks past on the street below in a lackadaisical manner, he’s in no hurry to get home this Christmas Eve, with his shopping bag for one, and I wonder why. Are you lonely?

As I hear the galloping fade off into the distance I bid this elderly man farewell and pour my love out of the window and down onto him to fill his heart with hope and love and to put a spring in his step.

5,742 Days: A mother’s journey through loss is free for a limited time only from the US Kindle Store and iBookstore.

Bunting’s anniversaries

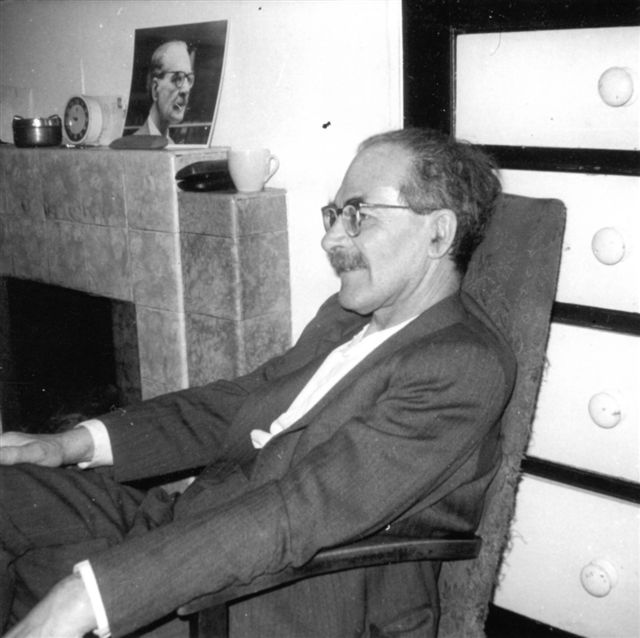

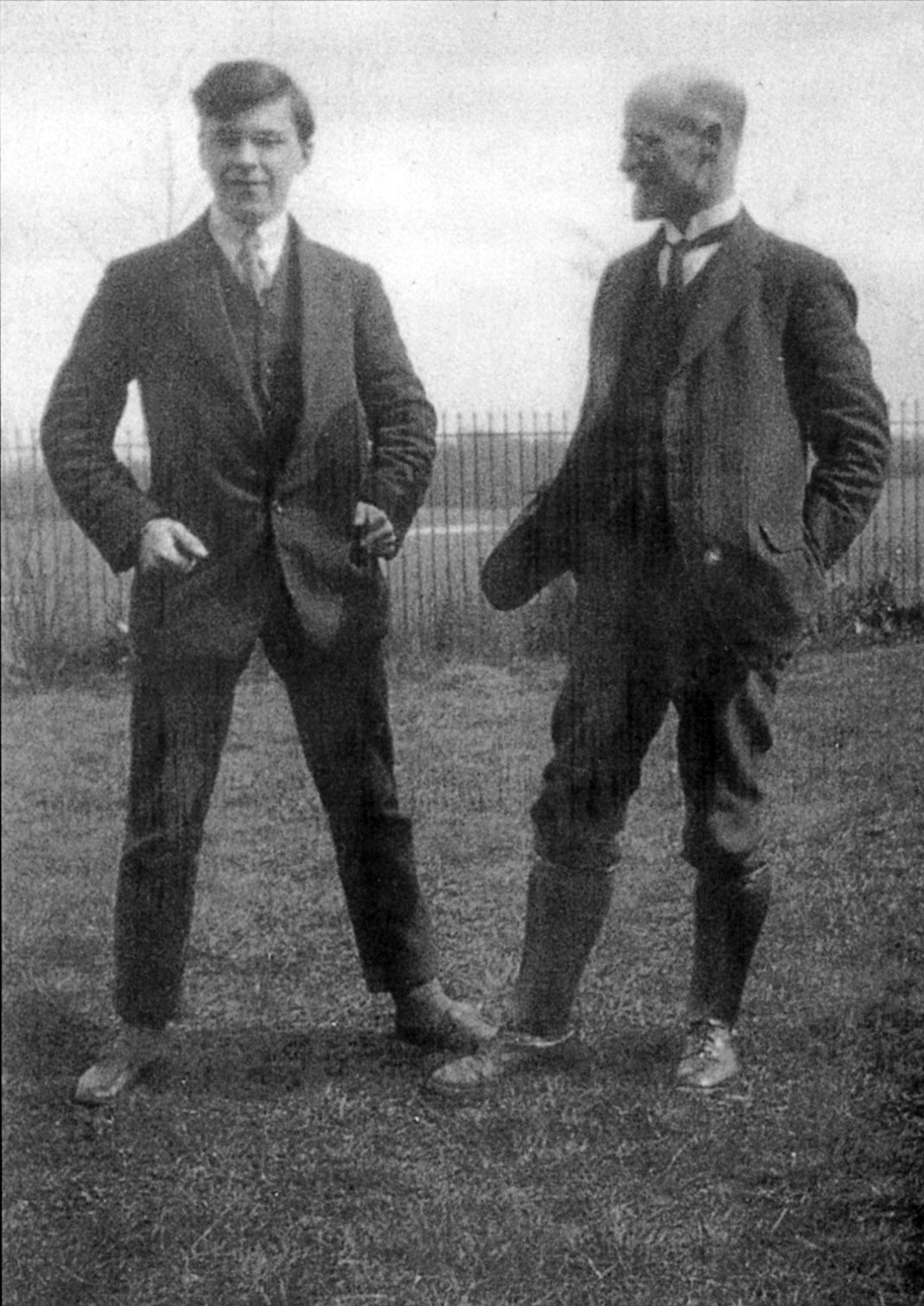

6 January 2014 by Infinite Ideas in Basil Bunting and A strong song tows us

by Richard Burton, author of A strong song tows us

Mark Ford, in his review of A Strong Song Tows Us in The Guardian, makes a connection that I haven’t seen anywhere else. “Of course,” he writes, “this biography has been written because in 1965 Bunting published Briggflatts, considered one of the greatest poems of the century.” Strangely enough it had never occurred to me that there was a semicentennial coming up but there’s no doubt that there is. Actually Ford is a little premature. The poem wasn’t published until the January 1966 edition of Poetry and didn’t appear in book form until the following summer, when Stuart Montgomery’s Fulcrum Press published it. But the first reading of Briggflatts was at the Morden Tower in Newcastle-upon-Tyne on 22 December 1965, so that allows us to claim an anniversary in 2015. A Strong Song Tows Us has had an odd relationship with Bunting’s anniversaries. I first introduced the idea of a biography of Bunting to the then publisher of his poetry, Oxford University Press, in 1995. The obvious publication date would have been 2000, the anniversary of his birth, but OUP weren’t interested and I shelved the project. And then Keith Alldritt’s imaginative reconstruction of Bunting’s life came out in 1998 and, in my view, did more damage than good to Bunting’s reputation.

In March this year I noticed another anniversary just as I was finishing the manuscript and putting the final touches to the introduction. I realised that it was 100 years to the month since Bunting stood in the Quaker burial ground in Brigflatts for the first time. In some ways that is the most important anniversary of all. As I wrote in A Strong Song Tows Us, it wasn’t just Brigflatts’ sprit of place that buoyed Bunting up through his tumultuous life. The clink of its stonemason’s chisel shaped his art. Meditation in the Quaker meeting house shaped his philosophy. His love for the stonemason’s young daughter, Peggy Greenbank, stayed alive through fifty years of separation.

Faber’s forthcoming edition of Bunting’s Complete Poems in 2015 will mark the 50th anniversary of Briggflatts’ appearance and will raise the profile of this extraordinarily neglected poet. It’s a shame it’s at least 75 years too late. We can blame T. S. Eliot for that.

For more information on the life and work of Basil Bunting, visit our dedicated site at www.basilbunting.com.

We might be the only ones in step – until you join us in Making your work work!

3 January 2014 by Infinite Ideas in Book publishing

by Jan Gillett, author of Making your work work

January 2nd – I’ve just handed over the marked proof of my book Making your work work: Everyday performance revolution to Rebecca at Infinite Ideas, and it’s a great feeling. My work is pretty much done now, they will enter the modifications, make a few adjustments to the design, and manage the final proofing and indexing. I get to see the final proof in February, then to the printer for publication in March, pretty much exactly on the schedule we agreed months ago.

All that’s great, it’s how their regular work in publishing books runs. I seem to be in step with that, it feels reassuring.

But I’m not quite so reassured about my subject, having just looked at the business section of our bookstore once again. Am I missing something? Am I the only one to think that a book that helps regular people to make ordinary work work properly would sell? Not one of the two hundred or so I can see claims to do that. Lots about hero figures, of academic studies, about a single aspect such as leadership or selling, and finance. But I spent two decades learning about the many aspects that have to be brought together to get consistent results, with little help from my training or guidance from bosses. Then two more decades teaching and helping others, integrating interpersonal aspects with analysis and learning.

We couldn’t find any others who had told this story, so when I was first thinking of writing a book, the absence of even one such potentially competing title was exciting. For there are many people who should be interested in making their work work better: more than a million with a management role in the UK alone. And many many more across the English speaking world. This is a big opportunity.

So now I have completed it, just sixty-odd thousand words, 200 pages. It all flowed logically to me it seemed, and to the friends and colleagues who have reviewed it on the go – thanks, folks. It shows any manager how to make their work work better by observing it in action, focusing it on customer-based aims, starting with small improvements, learning how to standardise and using problems to make permanent improvements. In particular it emphasises a four part model (The System of Profound Knowledge) developed after sixty years of practice by Dr W. Edwards Deming, and his PDSA Cycle for learning how to apply it. No other book that we can find comes close.

It felt natural to write it, and include so many themes we have explored with managers over the years in work as varied as aerospace, mobile phones, shipping, hospitals and so on. I even liked it when I read it again in the course of editing it over the Christmas break. But it still feels a bit odd to be on our own in the market.

So we will try to take advantage of being the only ones in step. Just because there may be only 1 out of 200 business books in the store related to this subject it doesn’t mean that only 0.5% of browsers would find it interesting. Just as Renault found with the Espace, Apple with the iPhone and Fosbury with his high jump, I think we might have a game-changing formula. I hope you will agree.

Perhaps in a year or three the rest of the business world will be in step with us. I hope so. And I hope of course that if you’ve read this far you will buy one on its publication in March (or indeed several … or more!), as I think you will find it helpful.

Anne-Marie Cockburn on publishing 5,742 Days

18 December 2013 by Infinite Ideas in 5742 Days, Book publishing

by Anne-Marie Cockburn, author of 5,742 Days

I get a call from my publisher to say copies of my book have arrived. I jump on my bike and cycle the two miles into town to collect a few copies. I bring them home and sit quietly looking at them – Martha’s beautiful face on the glossy cover stares out at me. Am I doing the right thing Martha, I wonder? Too late now, I add. What am I worried about? I suppose it’s fear of the unknown, which is fair enough – over the past few months I’ve had enough shocks to last a lifetime.

I think hard about why I’ve gone as far as publishing a book; it’s not something I planned strategically. The writing flowed out of me every day and this activity instantly made me feel better. I didn’t write thinking it would be read, which is why it’s written entirely without any self-conscious filter. The book is a by-product of my reaction to Martha’s death and my use of writing as therapy to help myself cope.

I needed to place my focus somewhere and make use of all that hope I had been channelling into Martha’s life. Having something to do, a new project to occupy me, distracts me from the darkness that echoes around my mind. The book is helping to shift the focus away from my first Christmas without her.

Today, the Guardian published my first official interview, which includes excerpts from the book. I was shaking last night as I thought about where this will all take me when my story is out in the public domain in such a raw form. I’m not media savvy and despite my inner strength, I’m also never too far from fragile, so I understandably don’t want to jeopardise my recovery by adding any undue stress. So I remind myself that writing has enabled me to gather my thoughts and journal experiences I would otherwise be likely to forget. Simple as that.

I don’t need to worry about how this is received by the wider media as the story really speaks for itself – no need for any embellishment or added drama, it’s sobering and grounding in its simplest format.

Anyway, I felt that the Guardian feature was a beautiful account and the overall tone was faithful to my voice and emotions. The headline is ‘Losing Martha’, which made my stomach churn as I glanced at it for the first time, next to her beautiful photograph. I read the story eagerly and was relieved that there was nothing to be concerned about.

One comment on the Guardian website read, ‘So stark. So beautifully written – but so hardwired from the heart, it is almost too painful to read.’ I like to think that this opinion will change once the reviewer has read the entire book, to something more like ‘Positive and uplifting, full of hope and determination’, but everyone is entitled to their opinion. At first glance, you would definitely think that my story would be too much to take – but in reality it is not like this; it’s a journey, an interesting, gripping and hopeful one.

My way of grieving is personal to me, but it’d be nice to think that I can show people that there is another way, one that can include laughter, joy and self-belief, alongside the inevitable emotional turmoil and anxiety. I’ve deliberately avoided wearing black and I’ve been tough with myself. For instance, if I was reminded of Martha in a specific shop, I’d force myself to go back there a few times so that the reference is no longer about her but about me. I don’t want to be constantly haunted but there are sixteen and a half years of rewiring to do and that would be an impossible thing to try to achieve.

I wonder how people felt as they read the article: did they have to stop and move on to something lighter such as the food section, relieved that they are not me, or did they persevere to the end? Did my story make them grab their children and hold them tight for a moment, glad that they’re safe and well? Or are there others out there like me who have outlived their own children, my story reminding them of their darkest hours?

I receive an email from a mother who saw a recent article written about me. She said, ‘…Heartiest condolences, I have no words that could properly express how sad I feel at what happened to your daughter. I would like to thank you for sharing your raw grief, I feel it will help other people a lot. Personally I will make sure my two daughters read your book before they try any drugs if they choose to. I believe children should be helped to make up their own decisions, and your work helps to show how dangerous a single moment can be and provide a perspective on the issue that is often lost. It is a great help to me as a parent to be able to present this information to my children.’

This email helps to banish any doubts that seep into my mind and confirm that what I’m undertaking is going to help others. It’s great to receive feedback of this type as it endorses what I hope to achieve over the next few months.

Today’s newspaper is relevant for 24 hours. It’s now 22:02, so as the piles of today’s newspapers are gathered up and dropped into recycling bins, my beautiful girl’s face looks up at them and fades like a ghost. I can’t close the newspaper and forget, I can’t sigh with relief and be grateful that it didn’t happen to me. I still struggle and find it hard to believe that it did happen, but I have to detach myself from the truth sometimes in order to cope. I wish I could glance through the article and be horrified for someone else – but I stop myself as I wouldn’t want to inflict what I’m enduring upon another living soul. I wish this wasn’t my story though, I don’t like this story. I’ll take my story to the library and swap it for another one – something lighthearted and fluffy would be nice.

2,221 forgotten poets of the First World War

3 December 2013 by Infinite Ideas in Book publishing

by Richard Burton, author of A strong song tows us

Liam Guilar’s thorough and thoroughly positive review of A strong song tows us in Lady Godiva and Me is a delight. Towards the end of his review Guilar raises some interesting points about how poets’ reputations are built and how the fact that they (sometimes) survive is at the mercy of the whirlpools academics create as they forge their own careers. It’s a point that he develops in his blog of 24 October 2013: “The shrinking of poetry from the public domain into academic institutions means that what gets read at school and taught at university, sets up a perverse kind of brand loyalty and what is read at school has more to do with what schools have to do, than with any kind of poetics. If no one ever published another poem, schools could continue blithely teaching their compulsory version of poetry because it has never borne much relationship to how poems operate outside.”

I hope his conclusion (that “Bunting is not appearing any time soon on a school curriculum”) is wide of the mark, but I suspect he is correct. The example he gives of my misunderstanding of the way the curriculum gives life to poetry is my assessment of the poets of WW1. He quotes this passage from A strong song tows us:

“We now think of the poetry of the first world war as overwhelmingly critical of political and military leaders’ strategy and tactics, articulating a sense of the hopelessness of valour in the teeth of insuperable horror, but that is largely because the poetry that has survived (because it is the best) was written by poets – Wilfred Owen, Isaac Rosenberg, Siegfried Sassoon and Robert Graves – who subscribed to the view that it was the futility and horror that needed to be in a perverse sense celebrated. In fact of the 2,225 poets who published during the years of the war hardly any expressed the views that have for generations of students defined its poetry.”

Guilar writes of this that “It’s the bit in brackets that betrays him: (‘because it is the best’.)

Is it? On what grounds?

…

Poems get chosen partly because of the syllabus requirement, but partly because of the values they espouse. Are those four poets Burton names really ‘the best’? Are there really no good pro war poems written by one of the 2,221 other poets?”

I have missed out an important part of Guilar’s argument here to save space but I’m not disagreeing with him. War poetry is not my area of expertise and I’m happy to be proved wrong about it, but it seems to me that the only way to advance the argument would be to give some examples of poems written by the other 2,221 poets that stack up against Futility, say, or Break of Day in the Trenches. Perhaps there are some gems to be found. It will be finding volunteers to read the works of 2,221 forgotten pro-war poets from 100 years ago that will be the challenge.

For more information on the life and work of Basil Bunting, visit our dedicated site at www.basilbunting.com.

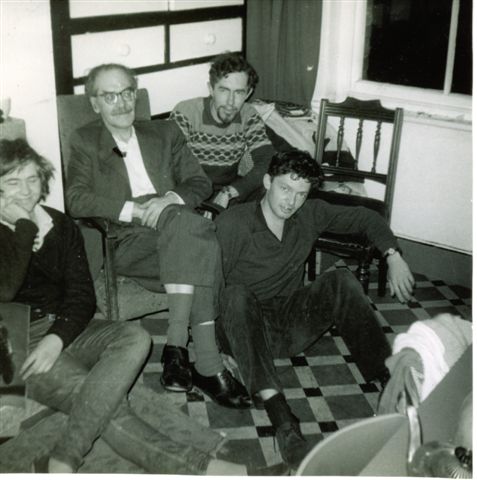

Bunting at Tom Pickard’s trial

27 November 2013 by Infinite Ideas in Basil Bunting and A strong song tows us

by Richard Burton, author of A strong song tows us

Liam Guilar, in his review of A strong song tows us, was sorry that I missed one of his favourite Basil Bunting stories: “It’s a fine book. There are a couple things I was surprised to miss: one of my favorite Bunting stories is about his appearance at Tom Pickard’s trial: Alldritt tells it briefly. Pickard tells it dramatically in More Pricks than Prizes building to a great exit line. But you can’t have everything.” The reason I didn’t tell it was that I was very dubious about the source and I hadn’t at that point seen Pickard’s memoir. Pickard was arrested in the mid 70s for his (relatively minor) part in a smuggled cannabis deal. As Pickard tells it:

“At the end of my long cross examination, it lasted a day and a half, I shakily resumed my seat next to [co-defendant] Costos while witness to my previous good character were drummed in. Amongst others, Eric Mottram and the film director, Lindsay Anderson spoke eloquently but the prosecutor ignored them until my final witness, Basil Bunting, took the witness stand…Bunting was someone the jury clearly felt comfortable with, which may be why the prosecutor rose to ask a question just as the old gentleman picked up his walking stick and was about to be helped from the witness box.

‘Wing Commander Bunting, would you still think so highly of Mr. Pickard if you knew that he took drugs?’

He smiled benignly and without a moment’s hesitation replied. ‘I would be surprised if a man of his generation didn’t.’

As Bunting walked out of the court Costos said, as much to himself as to those in earshot:

‘What a fucking beautiful old man.’”

From Tom Pickard, More Pricks than Prizes (2010) pages 63-68, by kind permission of Pressed Wafer.

ps. Pickard was found not guilty by a majority verdict.

For more information on the life and work of Basil Bunting, visit our dedicated site at www.basilbunting.com.