Wine and spirits

The Infinite Ideas interview with Julian Jeffs

12 November 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in Sherry, Wine and spirits

Julian Jeffs is the author of Sherry, sixth edition, available on 20th November. We’re all very excited about this and so Julian came along to discuss the sherry wine trade and his thoughts for the future of the drink.

Julian Jeffs is the author of Sherry, sixth edition, available on 20th November. We’re all very excited about this and so Julian came along to discuss the sherry wine trade and his thoughts for the future of the drink.

Why isn’t sherry produced anywhere else?

Sherry, like every other wine, is the product of vines and vineyards. The Palomino Fino grapes that produce sherry can be grown elsewhere and are found in various parts of Spain. In other places they produce rather inferior table wines and nothing in the least resembling sherry. The factors enabling these vines to yield sherry are the calcium-rich albariza soil and the climate, a combination unique to the sherry area.

What have been the biggest changes in the production of sherry over the years? Why do you think this is?

In the last sixty years practically everything has changed for two reasons. The first is the enormous increase in the cost of labour and the second is a much more profound knowledge of wine science: of what goes on while the juice of the grapes is being transformed into wine. The increased cost of labour has done away with the old gangs of workmen who used to run the bodegas in a very labour-intensive way. Mechanisation and efficiency became essential if sherry was to survive. And wine science means that diseased and defective wines have practically disappeared while the average quality of the wine has increased correspondingly.

In Sherry you’ve written a lot about the history of the drink, but what do you think lies ahead in the world of cognac; does it face challenges or do you predict a boom?

The history of sherry has been one of boom and bust. This is partly owing to the pendulum of fashion and partly brought about by the shippers who in times of boom go for volume and ship very poor wines at very low prices. This rightly brings them into disrepute. Its future can only lie in its being recognised as one of the world’s great wines, which it undoubtedly is. Another difficulty lies in the absence of advertising. The leading brands, which had to be of above average quality, were widely advertised but now that sherry is no longer profitable this is impossible. The market is being built up again for good quality wines and yes, I think here will be another boom, but the next peak may be many years away.

Do you think global warming has affected the production of sherry?

The only effect global warming has had on sherry so far is the advance the date of the vintage. This year it started on August 11th and ended on September 15th, about a fortnight earlier that it used to. The grapes are picked at the right degree of ripeness and it does not appear to have affected the quality in any way. It will be slightly easier, though, to make sweet wines.

Do you think that technology has generally been a good thing or a bad thing for sherry?

Technology has undoubtedly been a good thing in several different ways. Owing to the scarcity and cost of vineyard labour, without modern methods of cultivation and mechanical harvesting in particular, it is doubtful if the sherry vineyards could continue. In the bodegas extraction of the must from the grapes is now very well controlled so that the highest possible quality is obtained, with oxidation and excessive pressure avoided. The must is then be fermented under carefully controlled conditions and the poor quality or even defective wines that were once only too common have now virtually been abolished. I cannot think of any way in which technology has operated to the detriment of the wines save perhaps for the fact that it enables the shippers to pander to the taste for light coloured and limpid wines with too much taken out of them, leading to a diminution of flavour and character. But that seems to be the public taste.

Sherry is often regarded as an old-fashioned tipple; how would you convince today’s drinkers that it’s worth trying?

By giving them a glass or two to drink and telling them what to look for. I have given tutored tastings for sixth formers at schools and undergraduates at university who have been amazed and delighted when shown what good sherry really tastes like. The lesson that it tastes good with food is also being learned and shown by the success of tapas bars. The intelligent young can enjoy classical wines just as they can classical music.

Sherry-tasting is quite a specialised skill. How did you get into it – were you a natural or did you have to learn?

Some people have more sensitive palates and noses and better memories for flavours than others. Those who are favoured in this way make the best tasters, and there are a very few who do not seem to have these gifts at all, so almost anyone can enjoy the subtleties and beauties of wine. It does not come naturally, though, and has to be taught by suggesting to a young taster the things he or she should look for and to identify the differences between the various wines. I was fortunate in having a father who was a knowledgeable wine lover and who gave me my first lessons. Like most teenagers I was something of a rebel and saw there were two alternatives: I could reject wine, but that did not happen because I soon liked it enormously, or I had to learn more about it than my father. I chose the latter course to his amusement and gratification.

Can you tell us about the worst sherry drink you have ever tasted?

In 1956 I was crossing the Channel in a French ferry. Before lunch I went to the bar and optimistically asked for a glass of sherry. The barman told me he only had ‘French sherry’ so I ordered a glass. I have no idea what it was but it was memorably horrible. About twenty years later I was on holiday in Italy and saw a bottle of an excellent fino behind the bar. The colour looked wrong but I ordered a glass out of curiosity. I gathered it had been there, open, for two or three years and it had become brown. My curiosity was satisfied but again it was horrible.

Who is the greatest character you have met during your long career as a sherry expert? Can you tell us about him/her?

The Sherry country has always been full of characters and happily they still abound. I have met enough to fill a small book. But if I have to select just one it would be Manuel María González-Gordon, Marqués de Bonanza. He should be the subject of a biography not just a paragraph. I got to know him soon after I arrived in Jerez the first time in 1956 when he was head of González-Byass. He was tall, slightly stooping, as tall men often are, good looking, extremely short-sighted and never put on show any sign of his aristocratic birth, wealth or position. He drove about in an old Austin Seven. He was a scholar and a gentleman, friendly to all, young or old, saint or sinner. Drinking sherry with him was an education. To everyone he was Uncle Manolo. As a scholar he knew more about sherry than anyone and wrote the classic book about it. In his old age he laid the foundations for the scientific investigation of sherry that have given rise to its modern enology. Once when I was there the city pulled down its old gaol (which was a pity as it was in a rather beautiful old convent) and built a grand new one. I remarked on this to a friend who said “Yes, and there are only two people inside it: a gipsy who stole a hen and Uncle Manolo trying to help him.” A great friend of the United Kingdom, he was appointed hon. K.B.E. He was born a sickly baby and the doctors despaired of his life but his mother gave him sherry and he survived to die in 1980 aged 93.

Other than sherry what is your favourite drink – not necessarily alcoholic – and why?

I enjoy drinking all sorts of things ranging alcoholically from water to old brandy and taking in tea and coffee. I would miss them all, particularly coffee for breakfast. I enjoy drinking all the classic wines and several obscure ones but apart from sherry perhaps the one I would miss most (though by a very small margin over several others) would be claret.

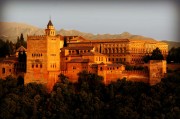

A brief history of Andalusia (and the wine that is made there)

10 November 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in Sherry, Wine and spirits

Most of you will know that sherry is made in the famous ‘sherry triangle’ in Spain, in the region of Andalusia. However, you may not know about the history of the region and the events which led to the production of sherry in such a concentrated area.

Of course, the reason sherry is produced there and nowhere else is due to the climate, the soil and the type of grape that produces the popular wine. Yet sherry is intrinsically Spanish and the perfect accompaniment to tapas. But what has happened in this region that gives sherry its character?

Firstly, Andalusia has been colonized by many different cultures, for over 6000 years, including the Greeks, Phoenicians, Romans, Jews and Muslims, bringing not only cultural but culinary diversity to this region. Its close proximity to the coast meant that major cities such as Cordoba and Granada were hotspots for migrant traders over the centuries.

Andalusia, known for a time as Al-Andalus due to the Islamic influence, was a key setting for the religious Reformation across Europe, and the infamous Spanish Inquisition. Such change has had an irreversible effect on the demographic of the area as well as the architecture, literature and artwork.

The stoic philosopher Sencea is said to have hailed from this region; clearly it has produced more than just the sherry grape.

However, it is still famous for its popular wine, which is thought to have been introduced to Britain around the time of the Spanish Armada in the 1500s. With such a long and colourful history, this region has produced one of the most distinctive wines in the world.

If you’d like to know more about the history of sherry, Julian Jeffs’ Sherry (sixth edition) will be published on 20th November and copies can be preordered now. A great read, it will make a gratefully received gift for those who are interested in history, wine – or indeed books!

The Infinite Ideas interview with Nicholas Faith

5 November 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in Wine and spirits

It’s Bonfire Night and we thought the perfect (grown up) accompaniment to this evening would be a lovely glass of cognac. Nicholas Faith is the author of Cognac and Nicholas Faith’s guide to cognac and recently he dropped in to discuss this renowned brandy. Here is what he had to say.

Why isn’t cognac produced anywhere else?

Because the Cognac region in Western France provides a unique blend of chalky soil and a temperate climate.

What have been the biggest changes in the production of cognac over the years? Why do you think this is?

In fact there’s only been one major change since the late sixteenth century, when the Dutch taught the locals to distil their rather acidic white wine. That’s an increase in the size of the stills in which the wine from which the brandy is made is distilled. The increase has little effect on the quality of the spirit.

In Cognac you’ve written a lot about the history of the drink, but what do you think lies ahead in the world of cognac; does it face challenges or do you predict a boom?

I’m optimistic. Despite a short-term downturn because of a fall in the Chinese thirst for Cognac the steady increase in the prosperity of so many countries means that more and more people can enjoy this delicious luxury.

I’m optimistic. Despite a short-term downturn because of a fall in the Chinese thirst for Cognac the steady increase in the prosperity of so many countries means that more and more people can enjoy this delicious luxury.

Do you think global warming has affected the production of cognac?

It merely enables the locals to harvest their grapes a few weeks earlier.

Do you think that technology has generally been a good thing or a bad thing for cognac?

Good to a limited extent in that it enables the producers to control the process more accurately. Otherwise there has been no effect.

Cognac is often regarded as an old-fashioned tipple; how would you convince today’s drinkers that it’s worth trying?

The big problem. First encourage them to try the cheaper cognacs as the basis for long drinks with soda, sparkling water or – in winter – with a ginger drink. As for the best ‘sipping’ cognacs tell them to forget balloon glasses and simply sniff and sip them in a wine glass.

Cognac-tasting is quite a specialised skill. How did you get into it – were you a natural or did you have to learn?

You might say that I fell into a cognac still by accident. A friend had moved from Bordeaux to Cognac and at the end of a well-liquidised evening I was converted and wanted to know more about this magic liquid. I then listened to the blenders which enlarged my appreciation of its complexities, especially those of the finest cognacs.

Can you tell us about the worst cognac drink you have ever tasted?

I’ve tasted lots of horrid spirits but never a truly awful cognac, the French authorities are too effective to allow such a drink through.

Who is the greatest character you have met during your long career as a cognac expert? Can you tell us about him/her?

André Hériard-Dubreuil who transformed Rémy Martin into a world-wide success. A brilliant, rugged visionary who saw no limit to his firm’s world-wide potential.

Other than cognac what is your favourite drink – not necessarily alcoholic – and why?

Mature claret, produced in the Médoc, the other side of the Gironde estuary – as complex and satisfying as cognac.

10 things you might not know about sherry

3 November 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in Sherry, Wine and spirits

Julian Jeffs’ book Sherry (6th edition), is due to be published on 20th November. We’re very excited and to get you in the mood, here are some facts about the drink that you might not know. Before you pour the last drop in your Christmas trifle, perhaps this year you’ll discover how exciting sherry is as a drink.

- Firstly, let’s get our bearings. For such a famous wine, sherry is only produced in the ‘sherry triangle’ in Spain, consisting of three towns, Jerez de la Frontera, El Puerto de Santa Maria and Sanlucar de Barrameda.

- Sherry has been connected to Britain for over 600 years. This is partly due to Catholics being exiled to Spain and setting up as wine traders who sent sherry back to Britain. Essentially, it has been part of British culture for over half a millennia.

- This wine is growing in popularity, particularly in the United States, where there is a trend for sherry cocktails in restaurants and even sherry tasting clubs have emerged, such is the appreciation for the wine.

- Rather than stick it in your trifle, how about having a glass of chilled fino with your tapas. Sherry is widely regarded as the perfect accompaniment to the Spanish meal.

- The wine was considered to be Shakespeare’s favourite drink. Perhaps a swig of amontillado will have you composing sonnets too.

- Legally, only sherry produced within the ‘triangle’ is allowed to be called ‘sherry’. However, it is produced in America and must be sold with the label, ‘California Sherry’ or ‘American Sherry’ so that consumers know the difference. This is due to a Spanish law that was created in 1933 to protect the term ‘sherry’ and make it exclusively Spanish.

- Christopher Columbus is thought to have stocked up his ship with many barrels of sherry before departing Spain for the New World, which, if true, makes it the first wine to make it to America. No wonder there is a growing popularity for it.

- Given that sherry is not as popular as other wines, it is often cheaper to buy and therefore you’re likely to get your hands on a quality bottle for a relatively low price.

- It can be split into different categories depending on their colour, oxidisation and blending.

- Rather than putting the cork back in the bottle and leaving it on your shelf for another year, sherry should ideally be treated like a white wine and consumed within a few days of opening, otherwise the wine becomes too exposed to oxygen and loses its flavour.

The Infinite Ideas interview with Richard Mayson

29 October 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in Wine and spirits

Port expert Richard Mayson has taken a few minutes out of his busy schedule to sit down with us and chat about his favourite drink. Here are his thoughts on port-related subjects from the tricks of tasting to the effects of global warming on the wine trade.

Port expert Richard Mayson has taken a few minutes out of his busy schedule to sit down with us and chat about his favourite drink. Here are his thoughts on port-related subjects from the tricks of tasting to the effects of global warming on the wine trade.

Why isn’t port wine produced anywhere else?

It is all a matter of terroir. Nowhere in the world apart from the Douro valley has the same combination of climate, geology/soil types and heritage. With centuries of accumulated history behind it Port is very much the product of a culture that has developed among 34,000 growers and the shippers (many of them well-known) who bring the wines to the market.

What have been the biggest changes in the production of port in recent years?

What have been the biggest changes in the production of port in recent years?

The main change that has taken place in recent years is the improvement in wine making technology. Until as recently as the 1970s a large amount of port was produced in time-honoured fashion that would be familiar to someone plucked out of the eighteenth century! Better knowledge of grape varieties, matching them to vineyard sites, picking at optimum ripeness and better control of extraction and fermentation have all made port into a much better product. Added to which, with their purchase of vineyards many of the larger shippers are now able to control the whole production process from the grape to the bottle. It is no wonder that the quality of port is better now than it has ever been.

In Port and the Douro you’ve written a lot about the history of the drink, but what do you think lies ahead in the world of port; does it face challenges or do you predict a boom?

Port has always faced challenges and always will. The Douro region is a costly place to grow grapes and wine is subject to the vagaries of fashion. I don’t predict a boom but I do predict a healthy future for those producers making less but better and focusing on quality-conscious markets. There is a real and developing interest worldwide in wines that embody the character of their grower and region. In the Douro small growers and large shippers have been facing up to this and there is much more individuality in their wines.

Do you think global warming has affected the production of port?

I am a global warming sceptic but, as a grape grower myself, it is hard to ignore the fact that something seems to have been going on with the climate over the past decade or more. The Douro is fortunate in having a spread of micro- and meso-climates and there is no reason why the region should not adapt. The grape varieties used to make port are amazingly drought resistant. There have been hot years (like 2003) but also cooler ones (like 2014). Vintage variation is what wine is all about and climate change adds a new and rather fascinating (if slightly scary) element to this.

Do you think that technology has generally been a good or bad thing for port?

Oh undoubtedly a good thing! But it has to be used wisely. When new technology has been rushed in, it has had negative consequences (as in the 1970s when I think there was a dip in the quality of vintage port). The port shippers have in general learnt from this and new inventions (like the robotic treading of grapes) have been introduced gradually.

Port is often regarded as an old-fashioned tipple; how would you convince today’s drinkers that it’s worth trying?

Port is a drink with a long history but it is just as relevant today as it always was. I defy any wine drinker not to be seduced by a glass of ten or twenty year old tawny served cool from the fridge on a warm summer’s day. It is about matching the wine to the mood and port with its multiplicity of styles is more than just a wine for drinking after dinner at Christmas!

Port-tasting is quite a specialised skill. How did you get into it – were you a natural or did you have to learn?

We all have to learn and I am still learning all the time. Every time I taste a new vintage I am learning something new. Taste is about memory and experience. I am fortunate in that I have plenty of both!

Can you tell us about the worst port you have ever tasted?

It would have to be something masquerading as port coming from another country. There are still some very poor, cheap imitations out there though fortunately they don’t tend to make it as far as the UK.

Who is the greatest character you have met during your long career in the port trade? Can you tell us about him/her?

I think it is the late and lamented Bruce Guimaraens who was the wine maker for Taylor and Fonseca until 1995. He made every wine from 1960 onwards including the great 1963, 1966 and 1970 vintages. Bruce was a huge man, in all respects, who knew every inch of the Douro and was treated with great regard and affection by growers and shippers alike. He spoke everyone’s language, in both Portuguese and English. He liked nothing better than a good glass of port and, eschewing the purple prose sometimes favoured by wine writers, he would drain the decanter and say ‘it’s just bloody good vintage port’. He is profiled on page 172 of my book [Port and the Douro].

Other than port what is your favourite drink – not necessarily alcoholic – and why?

I don’t drink much other than wine, water and tomato juice! I hate sweet, fizzy drinks and I don’t drink spirits. But I do like a bloody mary!

Richard Mayson is the author of Port and the Douro and Richard Mayson’s guide to vintage port

Port and lemon, madam?

29 September 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in Wine and spirits

We’re all aware of the centenary of the First World War and the commemorations will no doubt go on for many years to come. Undoubtedly the war changed the face of Britain, and indeed the world, irrevocably. We can thank this war for the invention of tanks, the poetry of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, and women’s suffrage. It also saw a change in our drinking habits.

Once the Treaty of Versailles had been signed and the world was left to rebuild, Britain’s drinking habits began to shift. One often thinks of port as a rather old-fashioned drink; in Port and the Douro Richard Mayson draws attention to the time that port became the fashionable tipple of the day:

‘In the aftermath of the First World War, ruby Port was drunk in huge quantities by the British and became strongly associated with the archetypal street-corner pub. It was often the basis for a long drink, ‘Port and lemon’ – a shot of ruby poured over ice, let down with fizzy lemonade and served with a slice of lemon. I have to admit to being a fan of the British soap opera Coronation Street (one of the longest-running TV series in the world) where Port and lemon was a special-occasion drink enjoyed at the Rovers Return by ladies like Hilda Ogden (when she wasn’t in her curlers). The fashion for Port and lemon began to fade in the 1960s and, sadly, the Hildas of this world are now few and far between. More recently, Liz MacDonald has been known to enjoy a Port and lemon now and then but ruby Port has now given way to proprietary brands like Archers and Baileys. Port and lemon was that sort of drink!’

So as we remember the fallen this year why not raise a glass of Port and lemon to their memory – we think you’ll enjoy it.