Basil Bunting and A strong song tows us

Basil Bunting and Lorine Niedecker

8 November 2013 by Infinite Ideas in Basil Bunting and A strong song tows us

by Richard Burton, author of A strong song tows us

In his Spectator review of my life of Basil Bunting, A strong song tows us, Wynn Wheldon asks if we ‘really need to read correspondence from someone who “nearly met Bunting”’, offering this as evidence that the book was ‘not terrifically well edited’. In my view A Strong Song Tows Us was expertly edited and it would be a shame if readers were discouraged from engaging with the life and work of Britain’s finest modernist poet by the suggestion that it wasn’t. The ‘someone’ in question here is the American poet Lorine Niedecker and it was only on the  occasion of writing this particular letter that they ‘nearly met’. As is made abundantly clear in the book they did meet and formed a close poetic association. Bunting regarded Niedecker as ‘easily America’s finest female poet’ and her ‘Ballad of Basil’ captures his poetic independence with the surest of touches. As the only woman to be associated with the Objectivist movement in American poetry and as a formidable poetic talent in her own right it seems reasonable to record her opinion of Bunting, especially as the particular letter to which Wheldon objects is the only evidence we have that Bunting nearly went into business as a commercial fisherman.

occasion of writing this particular letter that they ‘nearly met’. As is made abundantly clear in the book they did meet and formed a close poetic association. Bunting regarded Niedecker as ‘easily America’s finest female poet’ and her ‘Ballad of Basil’ captures his poetic independence with the surest of touches. As the only woman to be associated with the Objectivist movement in American poetry and as a formidable poetic talent in her own right it seems reasonable to record her opinion of Bunting, especially as the particular letter to which Wheldon objects is the only evidence we have that Bunting nearly went into business as a commercial fisherman.

She clearly loved his gravelly Northumbrian voice: ‘It was so pretty as we drove into our yard the evening we came home,’ she wrote to Cid Corman in October 1968. ‘So pr-r-r-r-it-ty as Basil said.’ She confided to Jonathan Williams that Bunting’s visit was a high point in her later life and by the end of 1967 she had completed ‘Wintergreen Ridge’:

Nobody, nothing

ever gave me

greater thing

than time

unless light

and silence

which if intense

makes sound

Unaffected

by man

thin to nothing lichens

grind with their acid

granite to sand

These may survive

the grand blow-up

the bomb

When visited

by the poet

From Newcastle on Tyne

I neglected to ask

what wild plants

have you there

how dark

how inconsiderate

of me

Niedecker and Bunting had the highest regard for each other. Her ‘The Ballad of Basil’, in mentioning Bunting’s influences, quickly identifies him as completely his own poet:

They sank the sea

All land

Enemy

He saw his boats stand

and he

off the floor

of that cold jail

(would not fight

their war)

sailed anyway

Villon went along

Chomei

Dante

and the Persian

Firdusi –

rigging

for his own

singing

Bunting said of Niedecker that ‘No one is so subtle with so few words’, and when she died in 1970 his daughter remembered her father’s anger that the event didn’t get the media attention he felt it deserved. A few years later he paid her a significant posthumous compliment: “There are some very fine female poets. One of the finest American poets at all, besides being easily the finest female American poet … – Lorine Niedecker never fails; whatever she writes is excellent.’ When Jonathan Williams was considering an edition of Niedecker’s poems in the 1960s Bunting was delighted. ‘Nobody else’, he complained, ‘has been buried quite so deep.’ He considered her a ‘much better’ poet than Emily Dickinson.

For more information on the life and work of Basil Bunting, visit our dedicated site at www.basilbunting.com

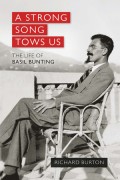

New release: A strong song tows us by Richard Burton

8 October 2013 by Infinite Ideas in Basil Bunting and A strong song tows us, Book publishing

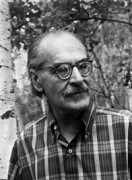

How can it be that one of the greatest and (eventually) most successful British writers of the 20th century could die in unmanageable poverty and be unremembered just twenty-five years after his death? Basil Bunting (1900-1985) was Britain’s greatest modernist poet and yet A strong song tows us: The life of Basil Bunting is the first biography of the poet to take account of all the available evidence. It was, as Matthew Sperling says in his glowing review, a life that ‘seems almost implausibly replete’. Bunting’s work was admired by the finest writers of the twentieth century, including W. B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway, Ford Madox Ford and William Carlos Williams. Pound edited Bunting’s first published poem, ‘Villon’, as ruthlessly as he had T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, and to the same stunning effect. His masterpiece, Briggflatts, catapulted Bunting to stardom and during the 1960s and 1970s he was the world’s most famous living poet, yet when he died he was practically penniless.

During his long life Bunting was an artists’ model, roadmender, sailor, balloon operator, diplomat, spy, journalist and lecturer. None of these was his true vocation – from an early age Bunting knew he was meant to be a poet. He lived in London, Paris, Rapallo, the US and Canada, and in Persia and Iraq, but his heart was always drawn to the north of England where he grew up and where he met the love of his life, Peggy Greenbank. Peggy remained in his mind throughout fifty years of separation until they were dramatically reunited after the publication of Briggflatts.

A strong song tows us shows why Bunting deserves to be recognised as a great modernist poet. Richard Burton explores Bunting’s fascinating life, takes a fresh look at some of his most important poems and unpicks the mystery of his disappearance from public consciousness. Click here to listen to a recent BBC Night Waves broadcast, in which Richard Burton discusses this topic with Anne McElvoy.

No twentieth century poet, not even Yeats, prickles the scalp quite as Bunting does. His voice is so assured, his lexical choices so deadly accurate, his timing so impeccable. You never find him reaching for effect, even when he delivers passages of the most precise, hard edged beauty:

Furthest, fairest things, stars, free of our humbug,

each his own, the longer known the more alone,

wrapt in emphatic fire roaring out to a black flue.

Each spark trills on a tone beyond chronological compass,

yet in a sextant’s bubble present and firm

places a surveyor’s stone or steadies a tiller.

Then is Now. The star you steer by is gone…

B. Bunting, Complete Poems, edited by R.Caddel (Newcastle upon Tyne, 2000)

- « Previous

- 1

- 2